The Forty-spotted Pardalote (Pardalotus quadragintus) is a rare Tasmanian bird that is now largely confined to Bruny Island, Maria Island and two small patches of forest on coastal mainland Tasmania. They rely on forests where their preferred food tree, white gums (Eucalyptus viminalis), are present to survive. As their former range has contracted, remaining populations now face several threatening processes, including low nesting site availability, competitors, ongoing habitat degradation, and parasitism by the larvae of an ectoparasitic fly that causes severe nestling mortality.

Given the current threats, understanding more about the remaining population is crucial for their future management. As part of a project supported by NRM South and funded in part by the Australian Government, researchers from the Australian National University’s Difficult Birds Research Group undertook the first comprehensive genetic assessment of the species.

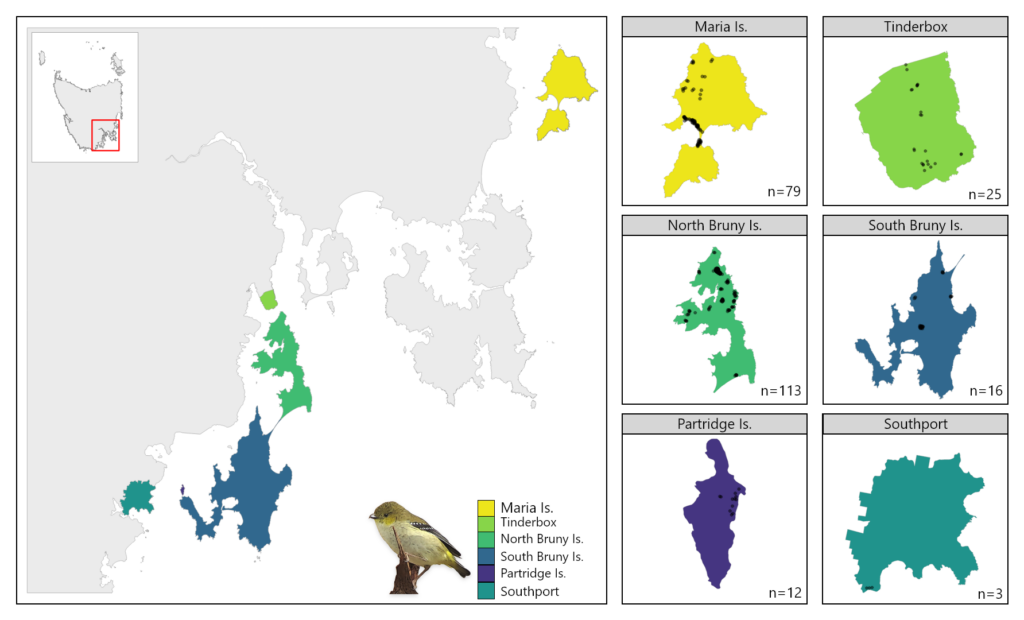

Sites where genetic samples were collected.

Researchers collected blood samples across the remaining populations which were then assessed in a laboratory. The good news is that genetic diversity is well distributed across remaining populations, with no signs of inbreeding an no immediate need for genetic management. However, ANU researchers recommend genetic monitoring, with Maria Island being a short-term priority due to the lower genetic diversity found in that population.

The study also found population genetic structure (a measure of genetic differentiation) corresponding to geographical barriers and fragmentation. The major genetic difference occurred between Maria Island and the southern populations.

“We found birds from Bruny Island on mainland sites which is encouraging and highlights the importance of Bruny Island for maintaining adjacent populations, and the potential for habitat and threat management to promote population expansion via colonisation.” Dr Alves said.

Another important finding was evidence of small effective population size. In simple terms, “effective population size” corresponds to the number of breeding individuals in the population. This finding shows that some populations might be vulnerable to a decline in genetic fitness which would increase their risk of extinction. These results highlight the importance of implementing actions that will increase population size, and to carefully plan management interventions.

“Translocation has been proposed as a management option to create insurance populations. However, given the small effective population size we found, and environmental pressures from existing threats, translocations would have to be carefully planned and shouldn’t be a priority at this stage. Sourcing birds for translocation efforts would rely on wild populations as there is no captive bred population, and intensive collection of founders can negatively impact the remaining source population.”

The researchers suggest that the priority management actions for the conservation of genetic diversity should focus on increasing effective population size and maintaining or enhancing connectivity among the southern populations via habitat restoration.

These actions should be complemented by ongoing genetic monitoring to assess the future need for direct genetic management actions, such as translocations to enhance genetic diversity if there is an observed decline.

This study has important implications for the management of forty-spotted pardalotes and shows that by assessing contemporary genetics, valuable information for conservation planning and decision-making can be produced to guide management actions.

Incorporating genetic monitoring alongside other habitat management actions will inform appropriate interventions and increase the chances of species recovery.

This study was published in the peer-review Journal Heredity and is freely available online at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41437-023-00609-6