Bringing new life back to an important wetland

Pitt Water-Orielton Lagoon sits near the mouth of the Coal River and is located halfway between the city of Hobart and its airport. Surrounded by largely agricultural and peri-urban landscapes, a new burst of life is currently unfolding in the heart of this internationally important Ramsar-listed saltmarsh wetland system thanks to the efforts of a three-year Blue Carbon project overseen by NRM South

Background

An internationally important wetland on Hobart’s doorstep

THE PROJECT

Managing the Process and Preserving Cultural Heritage

From securing funds to obtaining permits to collecting the final data points, NRM South managed this project from start to finish.

Our role as project managers is varied, and includes

- Relationship and stakeholder engagement,

- Communication,

- Landscape and logistical planning and agreements,

- Contract management of monitoring and on-ground works,

- Participation in monitoring,

- Permit management and reporting,

- Participation in associated research projects to share learnings

- Ongoing maintenance

Monitoring

Baseline data was collected followed by ongoing monitoring across a number of parameters to track changes across the site.

After Restoration – What has changed?

Since the project has wrapped up, the landholder continues to note improvements to the site. UTAS will continue to monitor fish, saltmarsh vegetation and changes in habitat use.

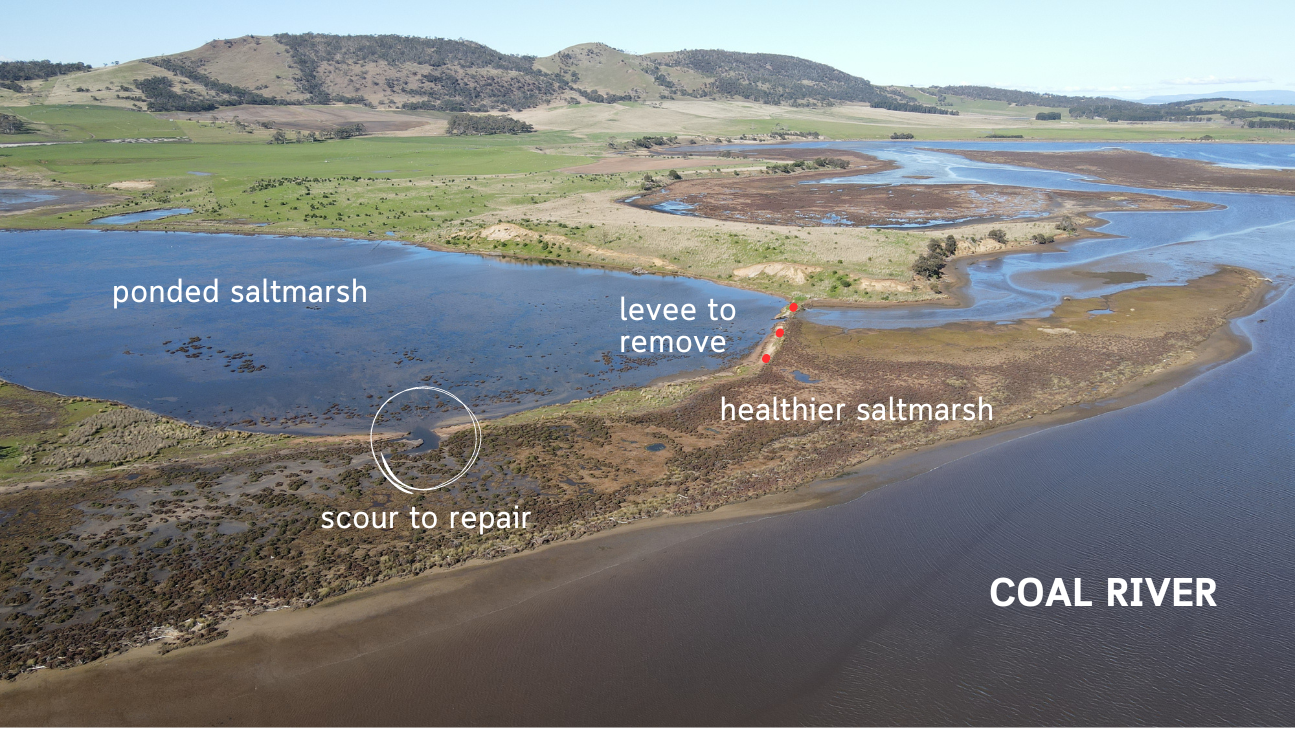

HYDROLOGY

Since the levee was removed, tidal pressure and flow have stabilized to represent normal, unrestricted tidal cycles. Prior to its removal, the hydrology of the site was erratic and not representative of regular tidal flow in the area. This created conditions where saltmarsh plants received too much or too little water.

FISH LIFE

An increased presence of fish (including green-back flounder, yellow-eye mullet, hardy head, goby and shark species) have been observed in the restored area compared with pre-restoration surveys. Crabs, snails and shrimp now also occupy the wetland sediment where there were previously none recorded. The size of fish accessing the restored area has also increased as, prior to the removal of the levee, only small fish were able to pass through.

VEGETATION

Within 12 months of the levee being removed, wetland vegetation has recovered by 20% in some observed areas.

BIRDS

The number of bird species recorded has increased from 29 species pre-restoration to 36 species post-restoration. This represents a 24% increase in bird species richness, with 13 new species recorded. New species records indicate a change in bird community composition and expanding use of the marsh by a broader suite of species. Foraging behaviour of some bird species has also been observed. Terns have been observed actively fishing within the marsh itself, a behavioural shift from pre-restoration use, when they typically foraged outside the marsh boundaries.

FENCING

The restoration area has now been fully fenced and sheep hoof prints and scats are no longer detected in surveys.A Blue Carbon Model and the EEA Approach

Blue Carbon is a term that is used for carbon contained in coastal and marine systems. At Pitt Water-Orielton Lagoon, this refers to the carbon that is taken up through plants and stored down in its sediments, as well as the carbon captured in standing vegetation.

Globally, saltmarsh wetlands can capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and lock it away at a far higher rates than terrestrial forests. But there are many other social, environmental and economic benefits that healthy wetlands provide – and measuring these co-benefits formed part of the Environmental Economic Accounting that was carried out as part of this project.

More than just a conservation success story

This project is supported by NRM South through funding from the Australian Government’s Blue Carbon Ecosystem Restoration Grants.