The swift parrot is a critically endangered migratory bird that divides its time between Tasmania and mainland Australia. The swift parrot gets its name from its impressive flight speeds, but there is another aspect of this small charismatic bird that is also swift – its rate of decline. The two major factors believed to be contributing to this decline are the loss of foraging and breeding habitat, and predation by the introduced sugar glider.

THE INTRODUCTION OF SUGAR GLIDERS TO TASMANIA

Sugar gliders were likely introduced to Tasmania sometime in the 1800s and they have gone on to become a major predator of swift parrots. Although their name suggests a nectar and fruit-based diet, sugar gliders also prey on insects, small animals and eggs – including nesting swift parrots. When nests are raided by the nocturnal sugar gliders the adult female birds are often killed, as they stay in their nesting hollows at night, and the resulting population imbalance between male and female birds contributes even further to their decline.

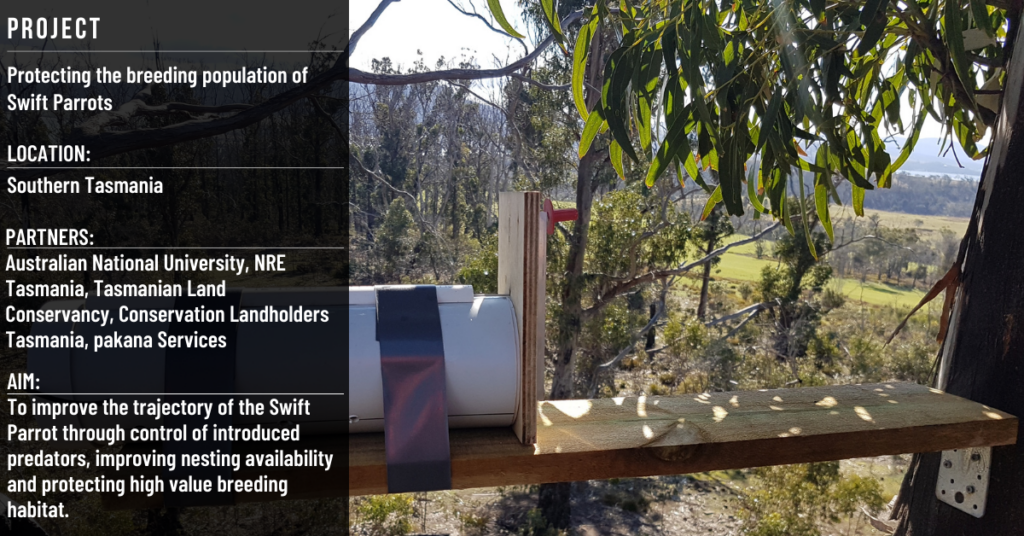

As part of an Australian Government funded project, NRM South has been exploring ways of reducing the impacts of sugar glider predation on breeding swift parrots. Four field trials carried out between 2019 and 2022 attempted to demonstrate an efficient and cost-effective way of controlling sugar gliders in swift parrot habitat.

These trials have had mixed results with progress impaired by a lack of understanding of sugar glider ecology in Tasmania. While there is a reasonable body of research on sugar gliders from mainland Australia, there a comparatively few studies from Tasmania. Understanding of their basic ecology, such as habitat preferences, home range size, diet, seasonal variation in vocalisations and breeding patterns, remains relatively limited.

Despite these knowledge gaps, the trials have progressed our understanding of how best to trap and control sugar gliders in Tasmania. As the project enters its final year, we review some of the key learnings:

Trapping sugar gliders is possible, but difficult

Our first two trials demonstrated that trapping sugar gliders has a highly variable success rate and is costly. Consistent success in trapping is hampered by a lack of understanding of how glider density varies with habitat type and how they use the habitats they occupy, as well as optimal trapping methods (including optimal trap spacing and height).

Different trap types have varying strengths and weaknesses

Mawbey traps, developed in Tasmania especially for sugar gliders, are a trigger activated baited trap. These traps caught the most gliders (captures on 6.4 % of trap nights in Trial 1, and 2.3 % in Trial 2). However, they need to be monitored daily once activated. As monitoring involves climbing trees, they can’t be used during unfavourable weather (e.g. on windy days). These risks could be mitigated if they can capture gliders successfully when mounted closer to the ground, which may also make them a cheaper option, but this requires further trials.

Box traps had a lower trap success (captures on 3.6 % of trap nights in Trial 1, and 2.2 % in Trial 2). Box traps are a nest box with a door that can be closed manually from the ground, trapping the animal inside. Box traps don’t stop animals coming and going until the door is operated, so don’t need to be checked daily. Trial 4 results showed that gliders’ use of box traps significantly increases the longer the traps remain in place.

Seasons may influence trapping success

The most successful of the four trials (in terms of the number of animals captured), was run from June-September (winter), suggesting there may be seasonal differences in how easy it is to trap gliders, but this requires further verification.

4G cameras are not a 100% effective trap monitoring tool

4G Infra-red cameras are activated when an animal moves in front of them (even at night), and the images are sent directly to an online database. Cameras were set up facing the traps and provided valuable information on how long it took the gliders to find and begin using the traps however they didn’t always capture critical moments when a glider either entered or left a trap. They are also limited by reception which can be patchy in areas relevant to swift parrot conservation.

A reactive approach to trapping is challenging to implement effectively

Swift Parrots breed in different parts of their range depending on where blue gums are flowering. Annual predictions of breeding locations are made in September based on eucalyptus flower bud surveys. In early trials, trapping sites were selected based on these predictions, but this approach had a number of issues;

- As Swift Parrots begin arriving in September, there is often insufficient time to select sites, gain approvals/permits, set up traps, and start trapping before the birds begin breeding.

- Not enough is known about sugar glider habitat preferences to be able to effectively choose sites where gliders are likely to be found in high densities.

As a result of these lessons, other approaches to glider trapping and control are currently being considered. In the project’s final year, NRM South will examine if extended sugar glider control (over 6-8 months) can effectively reduce the glider population in an area. We also hope to work with other funding partners on projects to research sugar glider habitat use and home range size. Ultimately, our aim is to gather enough information to be able to develop more effective glider control programs in the future to support on-ground conservation actions that can address the rapid decline of this critically endangered bird.

This project is supported by NRM South, in partnership with the Australian National University, NRE Tasmania, Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Conservation Landholders Tasmania and pakana Services, through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.